Inhalt:

- Theoretische Grundlagen

- Von aktuellen Leitlinien

- Fazit

- Postinfarkt-Algorithmus

1. Theoretische Grundlagen:

Pathological Ventricular Remodeling (Circulation 2013, Xie et al.)

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001879

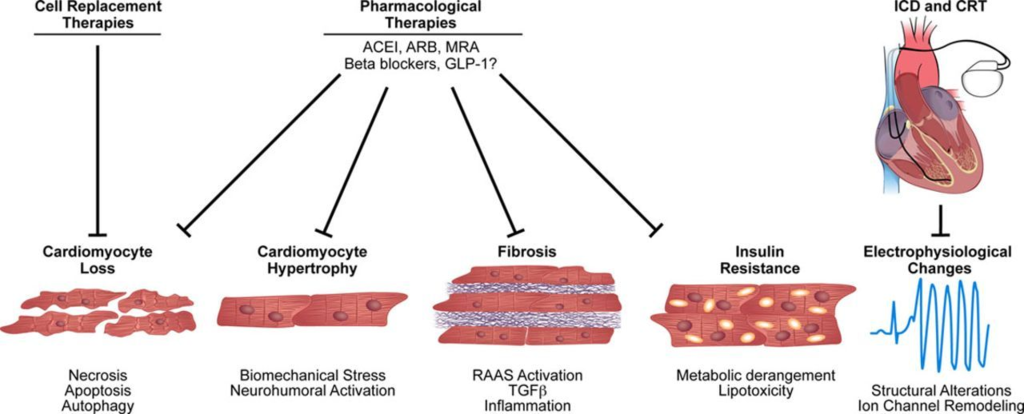

Mechanisms of pathological ventricular remodeling:

In response to pathophysiological stimuli such as ischemia/reperfusion or excessive mechanical load, multiple molecular and cellular processes contribute to ventricular remodeling.

These include cardiomyocyte loss through cell death pathways such as necrosis, apoptosis, or possibly excessive autophagy.

Cardiomyocytes become hypertrophic in response to both mechanical and neurohumoral triggers. Accumulation of excess extracellular matrix leads to fibrosis. Metabolic derangements, insulin resistance, and lipotoxicity can occur.

Finally, structural changes and alterations in ion transporting processes culminate in a proarrhythmic phenotype.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001879

Therapeutic interventions in pathological ventricular remodeling:

Clinically proven pharmacological agents reduce morbidity and mortality, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), β-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), by reducing cell death, hypertrophy, and fibrosis.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001879

Kardiales Remodelling nach Myokardinfarkt (Springer Medizin 2017, Ertl et al.)

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11298-017-5979-0

Medikamentöse Prävention und Therapie des Remodelling:

Nachdem zunächst Bemühungen, die Infarktgröße durch medikamentöse Interventionen zu reduzieren, zwar im Tierexperiment erfolgreich [28], im Einsatz am Menschen aber frustran waren, konnten Pfeffer et al. zunächst an der Ratte und dann auch am Menschen zeigen, dass ACE-Hemmer die negativen morphologischen und hämodynamischen Konsequenzen des Myokardinfarkts verhindern oder verzögern [29, 30].

Das Besondere der ACE-Hemmer in diesem Zusammenhang war, dass sie trotz ihrer auch vasodilatatorischen Eigenschaften nicht zu einer refektorischen Aktivierung des sympathischen Nervensystems und zu einer Refextachykardie führten. Schließlich zeigten Pfeffer et al. einen Überlebensvorteil von Ratten und dann in der SAVE-Studie auch von Patienten nach großen Herzinfarkten durch den ACE-Hemmer Captopril [31, 32] . Diese Ergebnisse wurden vollumfänglich in der SOLVD-Studie bestätigt und etablierten die sekundär-präventive Therapie von Patienten nach Myokardinfarkt mit ACE-Hemmern [33, 34]. Angiotensin-1-Rezeptor (AT1)-Blocker waren den ACE-Hemmern nicht überlegen [35]. Da initial die Intoleranz gegenüber ACE-Hemmern als hoch eingeschätzt wurde [36], wurden AT1-Blocker als Alternative evaluiert [37], konnten sich aber als Erstlinientherapie nicht durchsetzen.

Auch für Betablocker konnte gezeigt werden, dass sie ähnlich wie ACE-Hemmer das LV-Remodelling bei der KHK aushalten können, weshalb sie inzwischen zur etablierten Therapie bei der Prävention der ischämischen Kardiomyopathie gehören (Abb. 3; [38, 39]).

Mineralokortikoidrezeptorantagonisten (MRA) haben neben diuretischen Effekten eine antitrombrotische und endothelschützende Wirkung und reduzieren die neurohumorale Aktivierung [40]. Transgene Mäuse, die keinen myokardialen Mineralokortikoidrezeptor haben, sind gegen das ungünstige Remodelling geschützt [41, 42]. Die frühzeitige intravenöse Gabe des MRA Canrenoat , gefolgt von Spironolacton, verhinderte das Remodelling und supprimierte bei Patienten nach einem ersten Vorderwandinfarkt einen Marker für die im Remodelling induzierte Kollagensynthese über 4 Wochen (Abb. 4; [43]). Die Ausgangs-LVEF lag in dieser Studie knapp über 45 %, alle Patienten waren mit einem ACE-Hemmer, jedoch nur etwa ein Drittel mit einem Betablocker behandelt. Diese Ergebnisse konnten allerdings bis zu einem Jahr nach Infarkt in einem Kollektiv bestätigt werden, das eine Ausgangs-LVEF um 50 % hatte und dessen Patienten fast alle sowohl einen ACE-Hemmer oder AT1-Blocker als auch einen Betablocker erhielten [44]. Medikamentöse Interventionen an neurohumoralen Systemen waren also erfolgreich darin, ein Remodelling zu verhindern oder zu verzögern.

Zusammenfassung

Die Herzinsuffizienz ist eine führende Todesursache und häufigster Anlass für Hospitalisierungen in Deutschland, obwohl die therapeutischen Möglichkeiten v. a. bei reduzierter Pumpfunktion in den letzten Jahren erheblich zugenommen haben. Meist wird, bevor sich eine Herzinsuffizienz auch klinisch manifestiert, eine Phase des kardialen Remodellings durchlaufen. Remodelling wurde ursprünglich morphologisch und mechanisch definiert, vollzieht sich allerdings auch auf zellulärer und molekularer Ebene. So sind Heilungsvorgänge nach einem akuten Myokardinfarkt geprägt von Inflammation, zellulärer Migration und Narbenbildung. Das kardiale Remodelling wird zudem von systemischen Anpassungsvorgängen begleitet.

Ein primäres Ziel der Therapie sollte daher sein, das Remodelling zu verhindern. Wichtig sind hierfür die möglichst schnelle Diagnostik und Therapieeinleitung. Frühzeitige Reperfusionstherapie limitiert die Infarktgröße und trägt dazu bei, die linksventrikuläre Pumpfunktion zu erhalten.

Als medikamentöse Standardtherapie sind nach Myokardinfarkt Angiotensinkonversions- hemmer, Angiotensin-1-Rezeptor-Blocker und Betablocker etabliert. Auch Mineralokortikoid- rezeptorantagonisten zeigen günstige Wirkungen. Spezifische Medikamente, die darauf abzielen, schon in die Heilung des Infarkts einzugreifen, sind in Entwicklung.

2. Von aktuellen Leitlinien

- Up-to-date

- Deximed

- NVL

- ESC

- ACC/AHA

- NICE

Up-to-date (2020):

Betablocker

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/acute-myocardial-infarction-role-of-beta-blocker-therapy

While all patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) should receive long-term beta blocker therapy, the optimal duration, dose, and agent are not known. We recommend the use of a long-acting, once daily beta blocker to improve treatment adherence.

We believe the evidence supports the use of beta blockers in patients with MI for as long as three years. The evidence supporting a longer duration, or indefinite therapy, is limited. However, many patients with prior MI have an indication for continued beta blocker therapy such as heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction, hypertension, or angina.

We suggest doing so in patients with high-risk features at presentation such as cardiogenic shock, heart failure, or chronic kidney disease. For patients without these high-risk features, we suggest that practitioners discuss the potential benefits and risks of continued therapy with patients and have them participate in decision making. (See ‚Contraindications‚ below.)

Although the adjusted incidence rate of hospitalization for acute MI has declined by 4 to 5 percent per year since 1987, approximately 200,000 recurrent episodes of acute MI occur annually [39]. Whereas ischemic heart disease has become the leading contributor to the burden of disease as assessed on the basis of disability-adjusted life-years [40], and survival from acute MI is associated with the increasing incidence of heart failure in the United States, there exists a sound argument for prolonged, indefinite beta-blocker therapy post-MI.

We believe it is reasonable to discontinue beta blocker therapy, using a tapering protocol carried out over a few weeks, in patients with unacceptable side effects, for whom the financial burden is unacceptable, or in those for whom the use of multiple medications is problematic (polypharmacy). There are no known life-threatening side effects (such as proarrhythmia or malignancy) of long-term beta blocker therapy [41].

Many patients have been continued on this therapy indefinitely based on a 1999 meta-analysis of over 50,000 patients that showed a 23 percent reduction in death at a mean follow-up of 1.4 years [23]. In addition to the relatively short duration of follow-up, application of the conclusions of this meta-analysis is limited as reperfusion and medical (aspirin and statin) therapies were underutilized routinely. The findings in this meta-analysis were supported by a large observational study published in 1998 [21].

A more contemporary evaluation of the potential benefit from long-term beta blocker use was made in a 2012 observational study of over 14,000 patients with known prior MI enrolled in the international REACH registry [42]. Patients were enrolled in 2003 and 2004 and followed prospectively for up to four years. The primary outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke. Propensity score matching identified 3599 pairs of patients with and without beta blocker use. Aspirin and statin use (each) was approximately 75 percent. After a median follow-up of 44 months, there was a trend toward a lower incidence of the primary outcome with beta blocker therapy (16.9 versus 18.6 percent, respectively; hazard ratio 0.90, 95% CI 0.79-1.03). However, little difference was seen in the event rates in the beta blocker and no beta blocker groups as early as two years.

A 2013 observational study evaluated outcomes in 5628 patients with ST-elevation MI (STEMI) treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. During a median follow-up of nearly four years, mortality rates did not differ between patients with and without beta blocker therapy (5.2 versus 6.2 percent) [25]. The absence of a significant difference persisted after multivariate and propensity score matching. However, subgroup analyses revealed that beta blocker treatment was associated with a significantly lower mortality for only high-risk patients, such as those with heart failure.

ACE-Hemmer

A meta-analysis concluded that administration of an ACE inhibitor within 3 to 16 days of infarction can slow the progression of cardiovascular disease and improve the survival rate (figure 1) [1]. The mechanisms by which ACE inhibitors improve survival after MI will be reviewed here, beginning with a discussion of infarct expansion. The clinical data supporting the use of ACE inhibitors in this setting are presented elsewhere. (See „Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and receptor blockers in acute myocardial infarction: Clinical trials„.)

Attenuation of remodeling is thought to play an important role in the survival benefit associated with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors after myocardial infarction. These drugs also may have favorable effects on ischemic preconditioning, recurrent myocardial infarction and ischemia, sudden death, and fibrinolysis (reduction in plasma plasminogen activator inhibitor-1). (See ‚Reduction in recurrent myocardial infarction and ischemia‚ below.)

The effect of ACE inhibitors on infarct expansion reflects a chronic benefit. There is also experimental evidence that ACE inhibitors have more acute benefits, limiting the following changes that can occur during acute ischemia: myocardial injury, degradation of high-energy phosphate stores, and impairment of endothelium-dependent arteriolar responses [19,20]. These observations constitute part of the rationale for the early administration of ACE inhibitors (within the first 24 hours) after the diagnosis of acute MI has been made [21]. (See „Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and receptor blockers in acute myocardial infarction: Recommendations for use„.)

ACE inhibitors appear to reduce the incidence of recurrent myocardial infarction. As an example, the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement (SAVE) Trial of 2231 patients found that captopril was associated with a significant reduction in recurrent MI by 25 percent. This benefit was noted in all patient groups, including those who received other adjunctive therapies such as fibrinolysis, aspirin, and/or beta blockers [23].

ACE inhibitors reduce overall cardiovascular and sudden-death mortality [37]. There are several mechanisms that might contribute to the reduction in sudden death (see „Pathophysiology and etiology of sudden cardiac arrest„)

The addition of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or receptor blocker to standard medical therapy (including aspirin, thienopyridine, beta blocker, and statin) in patients with recent myocardial infarction improves cardiovascular outcomes.

Attenuation of remodeling is thought to play a critically important role in the survival benefit associated with ACE inhibitors after myocardial infarction. (See ‚Attenuation of remodeling‚ above.)

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists

For patients with STEMI who are receiving an ACE inhibitor and a beta blocker, and who have a left ventricular ejection fraction less than or equal to 40 percent and either HF or diabetes, we prescribe a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, also referred to as an aldosterone blocker or antagonist [3,4]. Therapy should be begun before discharge, since a mortality benefit is seen within 30 days [40]. The serum potassium should be monitored closely during treatment. Although uncommon, life-threatening hyperkalemia can occur due to the combination of aldosterone inhibition, reduced aldosterone secretion associated with ACE inhibitor therapy, and a progressive decline in renal perfusion induced due to HF. Elderly patients with renal insufficiency are at greatest risk. The use of aldosterone antagonists is discussed in detail elsewhere. (See „Secondary pharmacologic therapy in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) in adults“, section on ‚Evidence‘.)

Although a 2018 meta-analysis found benefit to the addition of aldosterone antagonist in patients with STEMI without heart failure and with an ejection of more than 40 percent, we believe significant limitations to this study prevent us from recommending this therapy for these patients [41,42].

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-non-acute-management-of-unstable-angina-and-non-st-elevation-myocardial-infarction

We recommend an aldosterone antagonist, also referred to as an aldosterone receptor antagonist or a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, to all NSTEMI patients who are receiving a therapeutic dose of an ACE inhibitor, have an LVEF ≤40 percent, have heart failure or diabetes mellitus, and are free of significant renal dysfunction or hyperkalemia [1].

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/secondary-pharmacologic-therapy-in-heart-failure-with-reduced-ejection-fraction-hfref-in-adults

The following are two partially overlapping indications for mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) therapy. MRA use is limited to patients whose serum potassium and renal function can be carefully monitored and who have baseline serum potassium <5 mEq/L; an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 is also generally required. (See ‚Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist‚ below.)

For patients post myocardial infarction (MI) with an LVEF ≤40 percent who are already receiving therapeutic doses of angiotensin receptor blocker and have either symptomatic HF or diabetes mellitus, we recommend the addition of an MRA.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-and-prognosis-of-heart-failure-with-preserved-ejection-fraction

Since the recommendation for MRA use in patients with HFpEF is weaker than the recommendation for MRA in patients with HFrEF, we dose MRA more cautiously in patients with HFpEF, using lower serum potassium thresholds for initiation, titration, and discontinuation.

Evidence to support this approach comes from the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) trial [31]. The trial randomly assigned 3445 patients with symptomatic HF and LV ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥45 percent to receive either spironolactone or placebo. The composite primary outcome consisted of death from cardiovascular causes, aborted cardiac arrest, or hospitalization for HF. The mean follow-up was 3.3 years.

The primary outcome of the overall study population occurred at a nominally but not statistically significant lower rate with spironolactone compared to placebo (18.6 and 20.4 percent, respectively; hazard ratio [HR] 0.89, 95% CI 0.77-1.04). Hospitalization for HF was less frequent in the spironolactone group (12.0 percent) compared with the placebo group (14.2 percent; HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.69-0.99) but other components of the primary outcome occurred at similar rates in the two treatment groups. Total deaths and total hospitalizations were similar in spironolactone and placebo groups.

The spironolactone group had twice the rate of hyperkalemia (18.7 versus 9.1 percent) and also a higher rate of increased serum creatinine levels but a lower rate of hypokalemia compared with the placebo group.

Subgroup analysis showed a significant reduction in the primary outcome with spironolactone among patients who were enrolled according to natriuretic peptide (BNP or N-terminal proBNP) criteria (15.9 versus 23.6 percent; HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.49-0.87) but not among those enrolled on the basis of hospitalization for HF in the past year. In the subgroup enrolled on the basis of natriuretic peptide criteria, spironolactone significantly reduced hospitalization for HF (11.2 versus 16.9 percent; HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.45-0.90) and was associated with a nonsignificant trend toward decreased cardiovascular mortality (8.2 versus 12.0%; HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.46-1.03).

Thus, for patients with clear evidence of HFpEF (including increased BNP) who can be carefully monitored for changes in serum potassium and renal function, we suggest adding spironolactone therapy to their medical regimens. The serum potassium should be <5.0 mEq/L and estimated glomerular filtration rate should be ≥30 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

Deximed (2019):

Betablocker

- routinemäßige Gabe von Betablockern insbesondere bei Patienten nach STEMI etabliert 35

- Betablocker sind auf jeden Fall indiziert bei einer LVEF ≤ 40 % und/oder Zeichen der Herzinsuffizienz. 31,35

ACE-Hemmer

- ACE-Hemmer sind indiziert bei LV-Dysfunktion und/oder Zeichen der Herzinsuffizienz oder bei Hypertonie. 31,35

- Ein Myokardinfarkt ist nicht per se eine Indikation für ACE-Hemmer, wenn der Blutdruck nicht erhöht und die kardiale Kontraktilität im Echo nicht eingeschränkt sind.

Aldosteronantagonisten

- Aldosteronantagonisten sind indiziert bei einer LVEF ≤ 40 % und/oder Zeichen der Herzinsuffizienz.

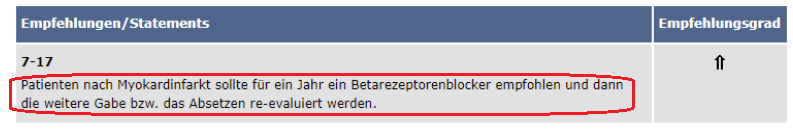

Betablocker

- Patienten nach Myokardinfarkt sollte für 1 Jahr ein Betarezeptorenblocker empfohlen werden und dann die weitere Gabe bzw. das Absetzen reevaluiert werden. 2

- Betablocker reduzieren die Herzfrequenz, senken den Blutdruck und verbessern so die Leistungsfähigkeit des Herzens.

- Die Häufigkeiten von Re-Infarkten werden im 1. Jahr nach Infarkt so vermindert.19 Im weiteren Verlauf besitzen Betablocker keinen Vorteil vor anderen Antihypertensiva.

- Darüber hinaus verringern sie das Auftreten von Arrythmien.

ACE-Hemmer, AT1-Rezeptorantagonisten und Aldosteronantagonisten

- Diese Medikamente sind nicht primär hilfreich in der Sekundärprävention bei KHK, kommen aber oft zum Einsatz im Rahmen eines gleichzeitig bestehenden Hypertonus oder einer Herzinsuffizienz.

NVL (2019):

https://www.leitlinien.de/nvl/html/nvl-chronische-khk/5-auflage/kapitel-7

Betarezeptorenblocker

Die strukturierte Suche nach Übersichtsarbeiten ergab einen systematischen Review der NICE-Guideline zur Sekundärprävention nach Myokardinfarkt. [263] Der Surveillance-Report der Leitlinie [292] identifizierte eine Metaanalyse von Bangalore et al. [[293]] als relevante neue Evidenz, die eine Aktualisierung des NICE-Reviews erforderlich mache. In unsere qualitative Analyse wird sowohl der NICE-Review als auch die Metaanalyse von Bangalore einbezogen.

Die Analyse von NICE schloss nur Studien ein, bei denen maximal 30% der Patienten an Herzinsuffizienz litten. Bei Initiierung der Betablockertherapie innerhalb von drei Tagen nach Symptombeginn (48 RCTs mit 77 719 Patienten, GRADE moderat) zeigte sich ein Trend zu einer reduzierten Gesamtmortalität (8,3% vs. 8,7%, RR 0,95 (95% KI 0,91; 1,0)). Ein knapp signifikantes Ergebnis bestand für den Behandlungszeitraum von bis zu 12 Monaten nach Myokardinfarkt (8 RCTs mit 19 406 Patienten, GRADE moderat, 11,2% vs. 12,2%, RR 0,91 (95% KI 0,84; 0,99)). Studien mit einem späteren Therapiebeginn (14 RCTs, 17 642 Patienten) zeigten einen deutlicheren Effekt auf die Gesamtmortalität (RR 0,76 (95% KI 0,69; 0,83)), ihre methodische Qualität wurde jedoch als sehr niedrig bewertet. [263]

Die Re-Infarktrate war bei initialer Betablocker-Therapie (13 RCTs mit 65 846 Patienten, GRADE low) um ca. 20% reduziert (2,1% vs. 2,5%, RR 0,81 (95% KI 0,73; 0,89)), entsprechend 5 verhinderten Myokardinfarkten bei 1 000 Patienten (3 weniger bis 7 weniger). Ein ähnliches Ergebnis zeigte die Analyse von Studien mit verzögertem Therapiebeginn (13 RCTs mit 17 089 Patienten, GRADE very low, RR 0,79 (95% KI 0,69; 0,91)). [263]

Die Wirksamkeit der verschiedenen Vertreter dieser Stoffgruppe ist nicht vergleichend untersucht worden. Nach Einschätzung der Autoren der NVL liegen bei Hypertonie und Z.n. Myokardinfarkt die besten Daten für Metoprolol vor, bei Herzinsuffizienz zusätzlich auch für Bisoprolol und Carvedilol. Vorteilhaft bei Patienten mit Diabetes mellitus oder COPD sind Beta-1-selektive Rezeptorenblocker ohne partielle antagonistische bzw. intrinsische sympathomimetische Aktivität (z. B. Bisoprolol, Metoprolol).

Ein Jahr nach Myokardinfarkt besteht aus Sicht der Leitliniengruppe keine eigenständige Indikation für einen Betarezeptorenblocker und die Gabe bzw. das Absetzen sollte daher re-evaluiert werden. Ihrer Einschätzung nach ist der Nutzen von Betarezeptorenblocker nicht ausreichend belegt für Patienten mit KHK, bei denen keine anderweitige Indikation zur Therapie besteht, z. B. auf Grund eines Hypertonus, einer Herzinsuffizienz oder spezifischen arrythmischen Indikationen. Bezüglich der Behandlung von Patienten mit KHK und linksventrikulärer Dysfunktion bzw. Herzinsuffizienz wird auf die NVL Chronische Herzinsuffizienz [53] verwiesen. Die abgeschwächte Empfehlung spiegelt die Unsicherheit bzgl. des Zeitraums von einem Jahr wieder.

ACE-Hemmer

Die strukturierte Suche nach Übersichtsarbeiten ergab zwei systematische Reviews von NICE zur ACE-Hemmer-Therapie bei Patienten mit KHK und erhaltener systolischer Pumpfunktion (LVEF > 40%).

NICE identifizierte einen RCT (n = 1 252, Follow-up 1 Jahr), der ACE-Hemmer bei Patienten nach Myokardinfarkt mit erhaltener LV-EF untersuchte. Dieser RCT zeigte keinen signifikanten Effekt auf die Gesamtmortalität und die Häufigkeit von Re-Infarkten, wobei seine methodische Qualität u. a. auf Grund einer hohen Abbruchrate als sehr gering eingeschätzt wurde. [263]

Bezüglich der Behandlung von Patienten mit stabiler KHK wurden drei RCTs identifiziert. Die Gesamtmortalität war unter ACE-Hemmern um 15% reduziert (2 RCTs, n = 11 047, Follow-up 3-5 Jahre, GRADE moderat, 9,2% vs. 10,8%, RR 0,85 (95% KI 0,76; 0,96)). Das Risiko für einen Re-Infarkt war ebenfalls signifikant geringer (3 RCTs, n = 19 337, Follow-up 3-5 Jahre, GRADE moderat, 7,4% vs. 8,6%, RR 0,86 (95% KI 0,78; 0,95)). [216]

Auf Ebene der Einzelstudien fand nur ein RCT einen signfikanten Effekt auf die Gesamtmortalität und Infarktrate [294]. Nach Einschätzung von NICE beruhen diese Effekte am ehesten auf abweichenden Baseline-Patientencharakteristika: Im Vergleich zu anderen RCTs litten in dieser Population mehr Patienten an Diabetes mellitus, der durchschnittliche Ausgangsblutdruck war höher und weniger Patienten erhielten Lipidsenker. [216]

Die Leitliniengruppe betrachtet eine KHK nicht als eigenständige Indikation für einen ACE-Hemmer: Ihrer Einschätzung nach ist der Nutzen von ACE-Hemmern nicht ausreichend belegt für Patienten mit KHK, bei denen keine anderweitige Indikation zur ACE-Hemmer Therapie besteht, z. B. auf Grund eines Hypertonus oder einer Herzinsuffizienz. Bezüglich der Behandlung von Patienten mit KHK und linksventrikulärer Dysfunktion bzw. Herzinsuffizienz wird auf die NVL Chronische Herzinsuffizienz [53] verwiesen.

AT1-Rezeptorantagonisten

Ein NICE-Review identifizierte einen RCT, der AT1-Rezeptorantagonisten mit ACE-Hemmern bei Patienten mit normaler linksventrikulärer Funktion nach Myokardinfarkt verglich (n = 429, Follow-up 60 Tage). Die Mortalität und die Myokardinfarktrate unterschieden sich in beiden Gruppen nicht signifikant [263]. Analog zu den ACE-Hemmern betrachtet die Leitliniengruppe eine KHK nicht als eigenständige Indikation für eine Behandlung mit AT1-Rezeptorantagonisten. Bezüglich der Behandlung von Patienten mit KHK und linksventrikulärer Dysfunktion bzw. Herzinsuffizienz wird auf die NVL Chronische Herzinsuffizienz [53] verwiesen.

Aldosteronantagonisten

Eine selektiv recherchierte Metaanalyse (10 RCTs, n = 4 147) fand eine signifikante Reduktion der Mortalität durch Aldosteronantagonisten bei Patienten nach STEMI (2,4% vs. 3,9%; OR 0,62 (95% KI 0,42; 0,91); p = 0,01). Kein Unterschied zeigte sich bei der Häufigkeit von Myokardinfarkten, den Neudiagnosen von Herzinsuffizienz und dem Auftreten ventrikulärer Arrhythmien. Ein Einschlusskriterium der Metaanalyse war eine erhaltene LV-Funktion (LVEF > 40%) [295]. Allerdings erfolgte in einer der eingeschlossenen Primärstudien keine Überprüfung der LVEF [296] und in sieben weiteren lag die durchschnittliche bzw. mediane LVEF zwar über 40%, eine linksventrikuläre Dysfunktion war jedoch kein Ausschlusskriterium. Ein unbekannter Anteil der Patienten hatte somit bei Studienbeginn eine linksventrikuläre Dysfunktion (durchschnittliche bzw. mediane LVEF in den eingeschlossenen RCTs 40%-52%, SD bis 12%) [297], [298], [299], [300], [301], [302], [303].

In der ALBATROSS-Studie, die das Gesamtergebnis der Metaanalyse wesentlich bestimmte, wurde außerdem keine LVEF-Bestimmung bei Studienbeginn durchgeführt, sondern erst zu einem unbestimmten Zeitpunkt bis sechs Monate nach Randomisierung. Zur Subgruppe der Patienten mit LVEF > 40% gehörten deshalb in der ALBATROSS-Studie auch Patienten mit initialer linksventrikulärer Dysfunktion, die sich im Studienverlauf unter optimaler Behandlung besserte. [299]

Nach Einschätzung der Leitliniengruppe können die Ergebnisse der Metaanalyse nicht sicher auf Patienten mit STEMI und erhaltener linksventrikulärer Funktion bezogen werden, da nur zwei der zehn Primärstudien ausschließlich Patienten mit LVEF > 40% einschlossen. Analog zu den ACE-Hemmern und AT1-Rezeptorantagonisten betrachtet die Leitliniengruppe eine KHK nicht als eigenständige Indikation für eine Behandlung mit Aldosteronantagonisten. Bezüglich der Behandlung von Patienten mit KHK und linksventrikulärer Dysfunktion bzw. Herzinsuffizienz wird auf die NVL Chronische Herzinsuffizienz [53] verwiesen.

https://www.kbv.de/media/sp/nvl_herzinsuffizienz_lang.pdf

ACE-Hemmer

In RCTs [153–156] und Metaanalysen [157,158] wurde nachgewiesen, dass ACE-Hemmer bei Patienten mit leichter, mäßiger und schwerer HFrEF (NYHA II-IV) die Gesamtsterblichkeit senken, die Progression der Pumpfunktionsstörung verzögern, die Hospitalisierungsrate senken sowie die Symptomatik und Belastungstoleranz verbessern. Bei herzinsuffizienten Patienten nach Myokardinfarkt senken ACE-Hemmer darüber hinaus die Re-Infarktrate [153–155].

Aldosteronantagonisten

Die Empfehlung zu Mineralokortikoidrezeptorantagonisten (MRA, auch: Aldosteronantagonisten) beruht auf inter-nationalen Leitlinien [13,17]. Nach Prüfung der dort zitierten Evidenz durch die Leitliniengruppe wurden Inhalt und Empfehlungsgrad übernommen. Der Nutzen von MRA bei chronischer Herzinsuffizienz wurde in mehreren randomisierten Studien belegt:

- Spironolacton 12,5-50 mg/Tag (RALES) [202]: NYHA III/IV, LVEF ≤ 35%, n = 1 663; Follow-up 24 Monate; Gesamtsterblichkeit signifikant reduziert (ARR 11%, NNT = 9); Rate der Krankenhauseinweisungen aufgrund der Herzinsuffizienz signifikant reduziert (ARR 29%, NNT = 4);

- Eplerenon 25-50 mg/Tag (EPHESUS) [203]: Patienten 3-14 Tage nach akutem Myokardinfarkt, LVEF ≤ 40%, mit Herzinsuffizienzsymptomen oder Diabetes mellitus, n = 6 632; Gesamtmortalität signifikant gesenkt (ARR 2,3%, NNT = 43); Komposit-Endpunkt Risiko kardiovaskuläre Sterblichkeit und Hospitalisierung aufgrund kar-diovaskulärer Ereignisse signifikant reduziert (ARR 3%, NNT = 34);

- Spironolacton [204]: NYHA I/II, LVEF ≤ 40%, Follow-up 6 Monate, n = 168; LVEF signifikant erhöht (p < 0,001), positive Effekte auf Remodeling und diastolische Funktion;

- Eplerenon (EMPHASIS-HF) [205]: NYHA II, EF ≤ 30% (≤ 35% bei QRS > 130ms), Hospitalisierung aus kardiovaskulären Gründen < 6 Monate oder erhöhte BNP-Werte, Follow-up 21 Monate, n = 2 737; Komposit-Endpunkt Risiko kardiovaskuläre Mortalität und herzinsuffizienzbedingte Hospitalisierung signifikant reduziert (ARR 7,7%, NNT = 13), Gesamtmortalität reduziert (ARR 3%, NNT = 33);

- Metaanalyse NYHA I//II, n = 3 929 [206]: Gesamtmortalität reduziert (RR 0,79 (95% KI 0,66; 0,95)), Rehospitalisierungen aus kardialen Gründen reduziert (RR 0,62 (95% KI 0,52; 0,74)).

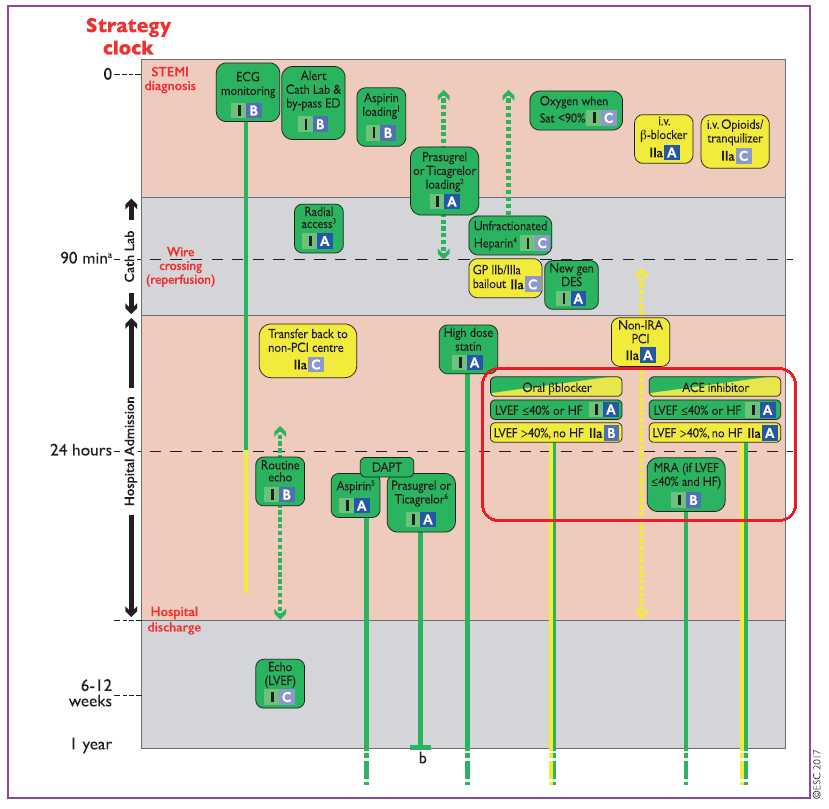

ESC (2017):

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/39/2/119/4095042 (STEMI)

Beta-blockers (Mid- and long-term beta-blocker treatment)

The benefit of long-term treatment with oral beta-blockers after STEMI is well established, although most of the supporting data come from trials performed in the pre-reperfusion era.353 A recent multicentre registry enrolling 7057 consecutive patients with AMI showed a benefit in terms of mortality reduction at a median follow-up of 2.1 years associated with beta-blocker prescription at discharge, although no relationship between dose and outcomes could be identified.354 Using registry data, the impact of newly introduced beta-blocker treatment on cardiovascular events in 19 843 patients with either ACS or undergoing PCI was studied.355 At an average of 3.7 years of follow-up, the use of betablockers was associated with a significant mortality reduction (adjusted HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.84–0.96). The association between beta-blockers and outcomes differed significantly between patients with and without a recent MI (HR for death 0.85 vs. 1.02; Pint = 0.007).

Opposing these results, in a longitudinal observational propensity-matched study including 6758 patients with previous MI, beta-blocker use was not associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular events or mortality.356

Based on the current evidence, routine administration of beta-blockers in all post-STEMI patients should be considered as discussed in detail in the heart failure guidelines;6 beta-blockers are recommended in patients with reduced systolic LV function (LVEF <_40%), in the absence of contraindications such as acute heart failure, haemodynamic instability, or higher degree AV block. Agents and doses of proven efficacy should be administered.357–361

As no study has properly addressed beta-blocker duration to date, no recommendation in this respect can be made. Regarding the timing of initiation of oral beta-blocker treatment in patients not receiving early i.v. betablockade, a retrospective registry analysis on 5259 patients suggested that early (i.e. <24 h) beta-blocker administration conveyed a survival benefit compared with a delayed one.362 Therefore, in haemodynamically stable patients, oral beta-blocker initiation should be considered within the first 24 h.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers

ACE inhibitors are recommended in patients with an impaired LVEF (<_40%) or who have experienced heart failure in the early phase.383,389–392 A systematic overview of trials of ACE inhibition early in STEMI indicated that this therapy is safe, well tolerated, and associated with a small but significant reduction in 30-day mortality, with most of the benefit observed in the first week.383,393 Treatment with ACE inhibitors is recommended in patients with systolic LV dysfunction or heart failure, hypertension,

or diabetes, and should be considered in all STEMI patients.394,395 Patients who do not tolerate an ACE inhibitor should be given an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB). In the context of STEMI, valsartan was found to be non-inferior to captopril in the VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarcTion (VALIANT) trial.396

Mineralocorticoid/aldosterone receptor antagonists

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) therapy is recommended in patients with LV dysfunction (LVEF <_40%) and heart failure after STEMI.397–400 Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone receptor antagonist, has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in these patients. The Eplerenone Post-AMI Heart failure Efficacy and SUrvival Study (EPHESUS) randomized 6642 post-MI patients with LV dysfunction (LVEF <_40%) and symptoms of heart failure/diabetes to eplerenone or placebo within 3–14 days after their infarction.397 After a mean follow-up of 16 months, there was a 15% relative reduction in total mortality and a 13% reduction in the composite of death and hospitalization for cardiovascular events. Two recent studies have indicated a beneficial effect of early treatment with MRA in the setting of STEMI without heart failure. The Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial Evaluating The Safety And Efficacy Of Early Treatment With Eplerenone In Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction (REMINDER) trial randomized 1012 patients with acute STEMI without heart failure to eplerenone or placebo within 24 h of symptom onset.401 After 10.5months, the primary combined endpoint [CV mortality, re-hospitalization, or extended initial hospital stay due to diagnosis of heart failure, sustained ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, ejection fraction <_40%, or elevated B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP)/N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP)] occurred in 18.2% of the active group vs. 29.4% in the placebo group (P < 0.0001), with the difference primarily driven by BNP levels.401 The Aldosterone Lethal effects Blockade in Acute myocardial infarction Treated with or without Reperfusion to improve Outcome and Survival at Six months follow-up (ALBATROSS) trial randomized 1603 patients with acute STEMI or high-risk NSTEMI to a single i.v. bolus of potassium canrenoate (200 mg) followed by spironolactone (25mg daily) vs. placebo. Overall, the study found no effect on the composite outcome (death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, significant ventricular arrhythmia, indication for implantable defibrillator, or new or worsening heart failure) at 6 months. In an exploratory analysis of the STEMI subgroup (n = 1229), the outcome was significantly reduced in the active treatment group (HR 0.20, 95% CI 0.06–0.70).402 Future studies will clarify the role of MRA treatment in this setting. When using MRA, care should be taken with reduced renal function [creatinine concentration >221mmol/L (2.5mg/dL) in men and >177mmol/L (2.0mg/dL) in women] and routine monitoring of serum potassium is warranted.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/37/3/267/2466099 (N-STEMI)

ACE inhibition

ACE inhibitors are recommended in patients with systolic LV dysfunction or heart failure, hypertension or diabetes (agents and doses of proven efficacy should be employed). ARBs are indicated in patients

who are intolerant of ACE inhibitors.478 – 480,530,531

Beta-blockers

Beta-blockers are recommended, in the absence of contraindications, in patients with reduced systolic LV function (LVEF ≤40%). Agents and doses of proven efficacy should be administered.482 – 486

Betablocker therapy has not been investigated in contemporary RCTs in patients after NSTE-ACS and no reduced LV function or heart failure. In a large-scale observational propensity-matched study in patients

with known prior MI, beta-blocker use was not associated with a lower risk of CV events or mortality.532

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist therapy

Aldosterone antagonist therapy is recommended in patients with LV dysfunction (LVEF ≤40%) and heart failure or diabetes after NSTE-ACS. Eplerenone therapy has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in these patients after ACS.487,488,525

ACC/AHA (2013/2014):

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1161/circ.110.9.e82 (STEMI)

Beta-Blockers

- All patients after STEMI except those at low risk (normal or near-normal ventricular function, successful reperfusion, absence of significant ventricular arrhythmias) and those with contraindications should receive beta-blocker therapy. Treatment should begin within a few days of the event, if not initiated acutely, and continue indefinitely. (Level of Evidence: A)

- Patients with moderate or severe LV failure should receive beta-blocker therapy with a gradual titration scheme. (Level of Evidence: B)

It is reasonable to prescribe beta-blockers to low-risk patients after STEMI who have no contraindications to that class of medications. (Level of Evidence: A)

Inhibition of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System

- An ACE inhibitor should be administered orally during convalescence from STEMI in patients who tolerate this class of medication, and it should be continued over the long term. (Level of Evidence: A)

- An ARB should be administered to STEMI patients who are intolerant of ACE inhibitors and have either clinical or radiological signs of heart failure or LVEF less than 0.40. Valsartan and candesartan have demonstrated efficacy for this recommendation. (Level of Evidence: B)

- Long-term aldosterone blockade should be prescribed for post-STEMI patients without significant renal dysfunction (creatinine should be less than or equal to 2.5 mg/dL in men and less than or equal to 2.0 mg/dL in women) or hyperkalemia (potassium should be less than or equal to 5.0 mEq/L) who are already receiving therapeutic doses of an ACE inhibitor, have an LVEF of less than or equal to 0.40, and have either symptomatic heart failure or diabetes. (Level of Evidence: A)

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/epub/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000134 (N-STEMI)

Beta-Adrenergic Blockers

- Oral beta-blocker therapy should be initiated within the first 24 hours in patients who do not have

any of the following: 1) signs of HF, 2) evidence of low-output state, 3) increased risk for cardiogenic

shock, or 4) other contraindications to beta blockade (eg, PR interval >0.24 second, second- or thirddegree heart block without a cardiac pacemaker, active asthma, or reactive airway disease).240–242

(Level of Evidence: A) - In patients with concomitant NSTE-ACS, stabilized HF, and reduced systolic function, it is recommended to continue beta-blocker therapy with 1 of the 3 drugs proven to reduce mortality in patients with HF: sustained-release metoprolol succinate, carvedilol, or bisoprolol.

(Level of Evidence: C) - Patients with documented contraindications to beta blockers in the first 24 hours of NSTE-ACS should be re-evaluated to determine their subsequent eligibility. (Level of Evidence: C)

It is reasonable to continue beta-blocker therapy in patients with normal LV function with NSTE-ACS.

241,243 (Level of Evidence: C)

Inhibitors of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System

- ACE inhibitors should be started and continued indefinitely in all patients with LVEF less than 0.40 and

in those with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or stable CKD (Section 7.6), unless contraindicated.275,276

(Level of Evidence: A) - ARBs are recommended in patients with HF or MI with LVEF less than 0.40 who are ACE inhibitor intolerant. 277,278 (Level of Evidence: A)

- Aldosterone blockade is recommended in patients post–MI without significant renal dysfunction (creatinine >2.5 mg/dL in men or >2.0 mg/dL in women) or hyperkalemia (K+ >5.0 mEq/L) who are receiving therapeutic doses of ACE inhibitor and beta blocker and have a LVEF 0.40 or less, diabetes mellitus, or HF.279 (Level of Evidence: A)

NICE (2013):

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG172/chapter/1-Recommendations#drug-therapy-2

Offer all people who have had an acute MI treatment with the following drugs:

- ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme) inhibitor

- dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin plus a second antiplatelet agent)

- beta-blocker

- statin. [2007, amended 2013]

ACE inhibitors

Offer people who present acutely with an MI an ACE inhibitor as soon as they are haemodynamically stable. Continue the ACE inhibitor indefinitely. [new 2013]

Titrate the ACE inhibitor dose upwards at short intervals (for example, every 12–24 hours) before the person leaves hospital until the maximum tolerated or target dose is reached. If it is not possible to complete the titration during this time, it should be completed within 4–6 weeks of hospital discharge. [new 2013]

Do not offer combined treatment with an ACE inhibitor and an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) to people after an MI, unless there are other reasons to use this combination. [new 2013]

Offer people after an MI who are intolerant to ACE inhibitors an ARB instead of an ACE inhibitor. [new 2013]

Renal function, serum electrolytes and blood pressure should be measured before starting an ACE inhibitor or ARB and again within 1 or 2 weeks of starting treatment. Patients should be monitored as appropriate as the dose is titrated upwards, until the maximum tolerated or target dose is reached, and then at least annually. More frequent monitoring may be needed in patients who are at increased risk of deterioration in renal function. Patients with chronic heart failure should be monitored in line with Chronic heart failure (NICE clinical guideline 108). [2007]

Offer an ACE inhibitor to people who have had an MI more than 12 months ago. Titrate to the maximum tolerated or target dose (over a 4–6-week period) and continue indefinitely. [new 2013]

Offer people who have had an MI more than 12 months ago and who are intolerant to ACE inhibitors an ARB instead of an ACE inhibitor. [new 2013]

Beta-blockers

Offer people a beta-blocker as soon as possible after an MI, when the person is haemodynamically stable. [new 2013]

Communicate plans for titrating beta-blockers up to the maximum tolerated or target dose – for example, in the discharge summary. [new 2013]

Continue a beta-blocker for at least 12 months after an MI in people without left ventricular systolic dysfunction or heart failure. [new 2013]

Continue a beta-blocker indefinitely in people with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. [new 2013]

Offer all people who have had an MI more than 12 months ago, who have left ventricular systolic dysfunction, a beta-blocker whether or not they have symptoms. For people with heart failure plus left ventricular dysfunction, manage the condition in line with Chronic heart failure (NICE clinical guideline 108). [new 2013]

Do not offer people without left ventricular systolic dysfunction or heart failure, who have had an MI more than 12 months ago, treatment with a beta-blocker unless there is an additional clinical indication for a beta-blocker. [new 2013]

Aldosterone antagonists

For patients who have had an acute MI and who have symptoms and/or signs of heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction, initiate treatment with an aldosterone antagonist licensed for post-MI treatment within 3–14 days of the MI, preferably after ACE inhibitor therapy. [2007]

Patients who have recently had an acute MI and have clinical heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction, but who are already being treated with an aldosterone antagonist for a concomitant condition (for example, chronic heart failure), should continue with the aldosterone antagonist or an alternative, licensed for early post-MI treatment. [2007]

For patients who have had a proven MI in the past and heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction, treatment with an aldosterone antagonist should be in line with Chronic heart failure (NICE clinical guideline 108). [2007]

Monitor renal function and serum potassium before and during treatment with an aldosterone antagonist. If hyperkalaemia is a problem, halve the dose of the aldosterone antagonist or stop the drug. [2007]

3. Fazit

- Remodeling ist ein sehr komplexer und nicht ganz abgeklärter pathophysiologischer Prozess

- Durch kardiale Ischämie (MI) oder Hypertrophie (HOCM, AS, Hypertonus etc.) entsteht Bild einer Herzinsuffizienz (meist kombiniert systolisch + diastolisch) mit möglichem Übergang in die Kardiomyopathie bzw. kardiogenen Schock

- Es gibt präklinische und klinische Hinweise, dass die RAAS-Blockade die Remodeling-Prozesse hemmt

- RAAS-Blockade involviert Betablocker, ACEI (+ARB) und MRA

- Aktuelle Datenlage von verschiedenen Autoritäten anders interpretiert, industrienahe Kardio-Gesellschaften natürlich weniger zurückhaltend (v.a. ESC)

- Betablocker

- Schon ein etablierter Remodeling-Hemmer (v.a. bei STEMI und HFrEF)

- In allen relevanten LL postischämisch empfohlen, fraglich bleibt die Therapiedauer

- Up-to-date: 3 Jahre,

- NVL+Deximed: 1 Jahr, dann Reevaluation nach Komorbiditäten

- ESC 1-3 Jahre,

- ACC/AHA: unbegrenzt

- NICE: 1 Jahr, dann Reevaluation nach Komorbiditäten

- Relativ gut belegte Reduktion der KV- und Gesamtmortalität nach dem MI (v.a. bei STEMI und HFrEF)

- ACEI

- Positive Rolle bei STEMI und postischämischer HFrEF gut belegt, sogar ein Grundstein der HFrEF-Therapie (schon ab NYHA I)

- Bei MI+HFpEF ziemlich widersprüchliche Datenlage

- ARB schlechtere Ergebnisse, nur bei ACEI-Unverträglichkeit

- Von LL verschiedene Empfehlungen

- NVL+Deximed: nur bei Komorbiditäten (HFrEF, Hypertonus, DM)

- ESC: bei STEMI (Ia bei HFrEF, IIa bei HFpEF), Therapiedauer nicht begrenzt

- ACC/AHA: bei STEMI eine Dauertherapie

- NICE: min. 1 Jahr

- MRA

- Noch wenig untersucht bei Z.n. MI (ESC IIb), obwohl schon positive Ergebnisse bei MI+HFrEF (EPHESUS, REMINDER, ALBATROSS)

- Bei HFpEF nur eine Metaanalyse (2018 Dahal et al.) mit dem Benefit aber kontroverse Methodik

- Spironolakton als MRA der Wahl (Eplerenon nur bei Gynäkomastie)

arznei-telegramm.de/html/2013_10/1310093_01.html - Indikation:

- Up-to-date: HFrEF oder NYHA III oder DM

- NVL+Deximed: HFrEF oder NYHA III

- ESC: HFrEF oder NYHA III oder DM

- ACC/AHA: HFrEF oder NYHA III oder DM

- NICE: HFrEF oder NYHA III oder DM

4. Postinfarkt-Algorithmus

- → Betablocker (z.B. Biso) 1 Jahr, dann Reevaluation nach Komorbiditäten

- STEMI?, HFrEF?, NYHA I oder mehr?, Hypertonus?, DM? → ACEI (z.B. Rami), so lange bis die Indikation gilt

- HFrEF?, NYHA III-IV?, DM? → MRA (Spiro), so lange bis die Indikation gilt

Fazit:

Betablocker sind eigentlich nach jedem Infarkt indiziert. ACE-Hemmer je nach Co-Morbiditäten, Aldosteronantagonisten wie ACE-Hemmer.

Wichtig ist, ein Jahr nach dem Infarkt durch einen klugen (!) Kardiologen die Indikation der einzelnen Medikamente kritisch überprüfen zu lassen.